September, 1995: “Gangsta’s Paradise” sits atop the Billboard charts, Sony’s PlayStation is released and the O.J. Simpson trial is plastered on television sets across the country.

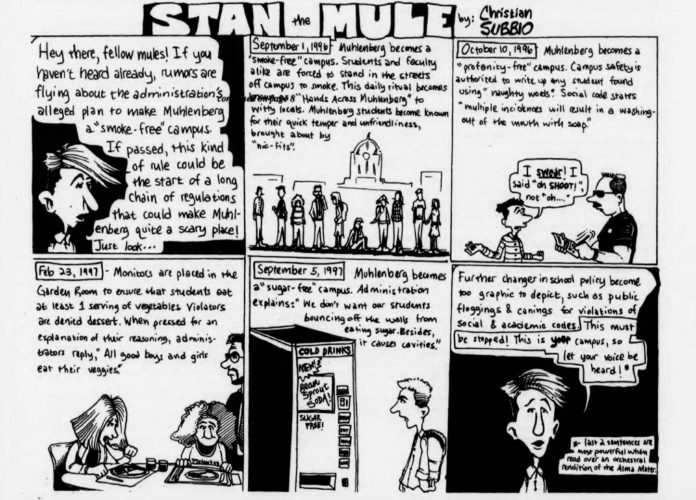

At Muhlenberg, plans for a smoke-free campus were finalized to mixed reactions.

“Muhlenberg is my home for four years and I don’t want to feel like I am a guest who can’t do as they please,”a student told The Weekly in ‘95. Others were supportive but expressed similar admissions-related concerns and potential impacts on alumni donations in the future.

The smoke-free campus movement is hardly a new phenomenon — it has followed in step with decades of policy and public opinion changes about smoking that are generally traced to the landmark 1964 report of the Surgeon General’s Advisory Committee on Smoking and Health. In 2003, Ozark Technical College in Missouri became the first institution of higher education to implement a smoke-free campus policy (For the record, Muhlenberg’s intentions to become smoke-free trace as far back as its 1993 five-year strategic plan.)

The push for a smoke-free Muhlenberg soon dissipated, and although the College has revised its smoking policy several times since, smoke-free efforts had not reemerged publicly until last month, when the Communications department ran a story about a research and policy proposal (full disclosure: it was my research).

With senior College officials poised to change an influential policy, now is the perfect opportunity to analyze the role of our current health and safety policies. Ultimately, the central question boils down to: what is the responsibility of a college to use policies to protect its students?

———

“I would start with this premise: when a government — or in this case, a college — regulates a freedom, the onus is on that institution to describe a compelling interest to enact that regulation, be it safety, liability or otherwise,” says Chris Borick, Professor of Political Science.

Often, our desires to exercise freedoms come in conflict with the government’s fundamental role in protecting our health, or, as the U.S. Constitution explains, to “promote the general welfare.”

This conflict is demonstrated perfectly at colleges, where the range of compelling interests — a legal standard used to determine whether a government has the authority to regulate or restrict an individual’s rights — is less broad because the population is more homogenous and the administration has a relatively unquestioned license to govern. Borick believes that colleges frequently have an easier path to demonstrating compelling interests because of liability concerns; that said, he cautions against the overuse of liability as an explanation for regulation.

“The college should be very transparent about how they draw conclusions on a new regulation, especially if it results in a great loss to students or others on campus,” says Borick. “It’s important to provide evidence in the explanation of why that loss is necessary.”

At Muhlenberg, 44 policies govern student behavior, many of which address health or safety in some meaningful way, ranging from alcohol consumption and drug use to weapons and smoking. It is safe to say, however, that most students have not read all — or perhaps, any — of them.

Some of the policies actually affect students even before they arrive on campus for their freshman year, such as the immunization policy requiring nine vaccinations (or a documented exemption for religious or medical reasons). But Brynnmarie Dorsey, Executive Director of Student Health Services, isn’t sure that expanding that requirement to include the influenza vaccine is appropriate.

Flu vaccines are generally about 40 to 50 percent effective, although this year’s estimates are closer to 35 percent. This differs greatly from the required vaccines, which almost always result in immunity. The lower effectiveness for flu shots leads Dorsey to believe that requiring them by College policy would go too far in restricting personal freedoms — a stance that reflects Borick’s emphasis on evidence-guided policymaking.

“Of course, I would love if we had 100 percent compliance,” says Dorsey. “I think that the College’s responsibility is to provide resources for students to reach their optimal level of well-being, be it physical, mental or spiritual, while also pursuing their academic interests.”

Additionally, many of these policies that govern health and safety are in place not only because of their impact on students, faculty and staff, but also for the surrounding neighborhood; certainly, these impacts are among Muhlenberg’s many compelling interests. For instance, the disruptive conduct policy keeps students from being too noisy and vandalizing or littering on a neighbor’s property.

“For me, it comes down to the community,” says Jane Schubert, Associate Dean of Students and Director of Student Conduct. But Schubert also admits that too often, policies are created or adjusted following an incident, and this presents particular challenges with respect to health and safety.

Take, for example, the case of Lehigh University, whose Interfraternity Council (IFC) announced in December that hard alcohol would be banned indefinitely at all IFC-sponsored events. The decision followed concerns of “extreme drinking” that led to nearly 150 alcohol-related citations in the first few weeks of the Fall 2017 semester. It would be foolish, however, to assume that this policy change will solve the larger problem — especially because non-IFC affiliated events are unaffected by the new policy.

With respect to alcohol, Muhlenberg is a ‘wet’ campus, meaning that students who are legally allowed to drink are permitted to do so, as long as they are not in the presence of minors and abide by the other components of the alcohol policy.

An essential part of the College’s Social Code, Schubert notes, is the Community of Responsibility statement. “It really guides how we need to exist on campus — all of these health and safety policies fall under this statement,” she says. Among other things, the statement requires students to “adhere to the highest standards of good citizenship” and “conduct themselves with … due regard for the rights and property of others.”

“Above all, what we want is clarity for our students. These policies are critically important because they shape and regulate our community as well as our neighbors,” says Schubert. “They provide context for action and thoughtful decision-making.”

Gregory Kantor served as the Editor-in-Chief from 2016 -2018 and majored in Public Health with a minor in Jewish Studies. In addition to his work with The Weekly, Greg served on Muhlenberg College EMS and worked in the Writing Center. A native Long Islander, he enjoys watching New York's losing teams – the Mets, Jets, and Islanders – in his free time.