Erica Hartman stands outside a home on the east end of Allentown, Pennsylvania, battling the unseasonably cold April air. Accompanying Hartman is a city police officer, who knocks to no answer. Hartman affixes a ‘sorry we missed you’ sticker to the door, fills in the contact information, and walks away.

As part of an initiative called the Blue Guardian program, the pair were at the home of someone who recently overdosed on opioids. It’s more common to make contact with the individual, says Hartman, and when they do, the impact can be immediate.

“These individuals need help but may not know how to ask at such a vulnerable time. Now we’re at their door, giving them help” says Hartman. “I really believe that Blue Guardian has been a God-send to our community.”

Last year, there were officially 300 opioid-related overdoses in Lehigh County, which comprises Allentown and its westward suburbs, but officials estimate that thousands more are battling related addictions. In a country where 115 people die daily from opioid overdoses, however, this individual is comparatively fortunate.

No one in the city of Allentown or the greater Lehigh Valley is waiting for the federal government to swoop in, wave a magic wand and solve the crisis. Although the Trump administration has identified the opioid epidemic as a priority, action — and more importantly, funding — has hardly matched the rhetoric. Thus, counties like Lehigh have turned to state- and local-level politicians, as well as community-based experts, to begin to earnestly address the problem. For example, Hartman is a certified recovery specialist who now routinely participates in the county’s innovative, six-week old Blue Guardian program. When opioid overdose victims are revived using naloxone — the life-saving overdose reversal drug — they are met by experts at their home. This program is just one of several different steps that Lehigh has taken to combat this multi-faceted crisis.

In many ways, America’s opioid epidemic is truly a local problem — and local problems are often best addressed with local solutions.

The truth is that people around the world have pain, but the United States is the only country dealing with a crisis of this magnitude,” says Kate Richmond, associate professor of psychology at Muhlenberg College. According to Richmond, three factors are having the greatest influence: the pharmaceutical industry’s stranglehold on healthcare delivery, high levels of trauma and violence, and the relative intensity of news and information.

“Health and healthcare have become synonymous with medication and taking a pill,” says Richmond. “There is something normative in our society around the idea that medication can solve many of the healthcare problems that we face — this is not true in other parts of the world, where understanding contexts and environmental stressors plays a larger role.”

This reliance on pills is compounded by what Richmond calls “a tipping point of trauma” that the country faces — between veterans returning home from multiple wars and tours of service and increasing rates of violence in communities, Americans too often find themselves in a constant state of hypervigilance. Added to this is the so-called “post-truth era” and the sheer amount of information available, where emotional appeals and the 24-hour news cycle reign supreme.

Turning to medication — be it an opioid or alcohol, for example — can help mitigate these problems, at least in the short-term. The beginnings of an addiction, of course, derive from here: as an individual builds tolerance, higher doses or amounts are necessary.

“The opioid epidemic is sincerely a public health issue and has become a machine with no start or end,” says Richmond. “You can target Big Pharma, you can target trauma rates, but because they’re so interconnected, focusing on just one is a band-aid approach.”

Though the factors are undoubtedly interrelated, the pharmaceutical industries’ influence on American healthcare — at least with respect to opioids — does have a traceable starting point. In January 1980, two doctors from the Boston University Medical Center sent a letter to the editor of the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine. The correspondence, which was not a clinical trial or epidemiological study, stated that among the 12,000 patients at the hospital who had received narcotics (including opioids), only four were considered addicted. Of course, the case study addressed in the letter is not representative of the real circumstances surrounding opioid use — the medications were delivered in small, regulated doses under the watchful eye of clinical staff in a hospital setting; hardly the experience that Americans have with prescription opioids today.

In the decades that followed, popular press sources began citing the letter as a “landmark study;” outlets from Scientific American to Time magazine fell victim. However, Purdue Pharma may be most culpable, as it trained sales representatives to cite the study — and the less than one percent addiction rate — in marketing pitches to doctors about the relative safety of its drug, Oxycontin. Sales ballooned from $48 million when the drug was introduced in 1996 to over $1 billion in just four years, and even though the company paid a $635 million fine for false advertising in 2007 and recently announced in February of 2018 it would no longer market Oxycontin to doctors, the drug still represents the primary revenue stream for a $3 billion company.

It would be easy to mistake the Treatment Trends Center of Excellence, located on 5th Street in east Allentown, as a church; its all-brick exterior, white cross topper and bright red doors do not necessarily bespeak a drug addiction treatment center or halfway home. In its past life, the space was a recreational hall for St. John’s Lutheran Church, located just across the street. But the days of high school dances and volleyball games are long gone — inside now are six dedicated employees who, in the course of the last year, have touched the lives of nearly four hundred individuals.

Michelle Steiner, the center’s care manager and project director, has decades of experience in treating addiction in roles ranging from counselor, case manager and assessment specialist. Her desk, cluttered with client paperwork and program information, is located in a rear corner of the room near the coffee machine — perhaps intentionally so, because hardly a minute goes by without a client stopping for some ‘coffee and community,’ as the staff calls it. These informal contacts are an essential component of their treatment philosophy, and the office’s location facilitates it: one must walk through it to enter the Halfway Home of the Lehigh Valley, a 40 bed, mixed-sex facility designed to help individuals become more independent through counseling services and employment assistance.

Treatment Trends has offered addiction treatment services to residents of the Lehigh Valley since 1969, but two years ago, expanded its services to specifically address the opioid epidemic. In summer 2016, Governor Tom Wolf announced the state’s Center of Excellence program, which would provide additional funding to preexisting organizations as part of a three-year grant. These centers, which now number 45 across the state, provide care to only Medicaid recipients, the joint federal-state health insurance program for low-income and disabled Americans. Care managers help integrate primary care and behavioral health as part of a holistic approach to treatment, including access to popular medication assisted treatments like Vivitrol, Suboxone or Methadone, which help individuals manage the opioid withdrawal process.

“It’s about building bridges between treatment and the community,” says Steiner. “And this grant allows us to do things that others cannot. Because we’re grant-funded, we don’t have the constraints of reporting to insurance companies or billing for services. For example, a care manager met with one of our clients who had just been placed at Victory House [a homeless shelter in nearby Bethlehem]. He came to us extremely intoxicated and we successfully helped through treatment but when he came out of treatment, he started living at a warming station. So, we went down one morning at 7:00 to grab his clothing and bring him over to Victory House. These are the things we do daily that would not be considered ‘billable,’ but we do them anyway. Having that freedom of not having to bill insurance or worrying about ‘Is this covered?’ makes it easier to get on the ground and do what we have to do.”

This idea of ‘getting on the ground’ is similar to the staff’s philosophy of ‘meeting people where they are’ and connecting with the community. The center encourages walk-ins, which constitute over a third of their referrals, though other sources include inpatient and outpatient drug and alcohol facilities and the judicial system. Steiner says she hardly leaves home without Center of Excellence brochures or the neon yellow business card-sized information sheets, which she drops everywhere from bus stations to grocery stores. But perhaps the center’s best work in ‘meeting people where they are’ is the Blue Guardian program.

Currently, when naloxone is administered to an individual who overdosed on opioids by police officers in Allentown or nearby South Whitehall and Salisbury Townships, one of Treatment Trends’ certified recovery specialists is notified. Within 48 to 72 hours of the individual returning home, a law enforcement official and the recovery specialist coordinate an unannounced home visit. The hope, of course, is that this personal touch can aid in connecting them to treatment and other services, but perhaps just as importantly, it strives to extend services to the family. The nearly two-month-old program is very much a work in-progress — Steiner acknowledges that those revived by the fire department or emergency medical services are currently falling through the cracks, though the expectation is that the program will be expanded in the coming months.

The Blue Guardian program is the brainchild of Layne Turner, Lehigh County’s Drug and Alcohol Administrator. In addition to Blue Guardian, his office ensures that first responders across the county are trained in, and have access to, naloxone and provides support to the Hospital Opioid Response Team (HOST), the first-line attempt to connect individuals to treatment. This so-called ‘warm hand-off’ process occurs between clinical staff in the hospital and a HOST team member, and after just one year in place, the results are impressive: in 2016, the year before HOST was rolled out, Turner says there were a total 39 hospital-to-treatment referrals, despite more than 300 overdoses occurring each month. In 2017, the program saw nearly 1,000 residents of the county go directly from the hospital into treatment.

“The message of these programs is: ‘We are here to help you and your family, we are here to be that person you can call. You’ll see me on street again, you’ll see me in your community. Reach out to us and we will help you and help you get into treatment.’” says Turner. “And so far, those outreach programs are going extremely well, where families are so welcoming of the opportunity to talk to a certified recovery specialist or a police officer and share with them life events and learn about available resources. It’s really starting to change the way our community is looking at this problem.”

This attention given to the family has been particularly important, especially considering that in some cases, they are unaware of the problems that their other family member is struggling with. In particular, Hartman says that extending resources to the family is a crucial component of the Blue Guardian program, as well as the other services that Treatment Trends offers.

“As soon as I knock on that door, the family is seeing me with a police officer, and that can certainly be a shock. But then we immediately see the relief on their face, that there’s help out there,” says Hartman, who in addition to her role as a recovery specialist, has training in family therapy and child advocacy. “So yes, the physical trauma has been done to the addict given their drug use, but the longer-lasting emotional trauma is for the family. It’s so important that we recognize this.”

And Turner speaks of three groups: families who are directly affected by the opioid epidemic, families who are indirectly affected and families who have been unaffected or sheltered completely. The problem is, as Turner notes, that these groups have created silos and do not engage with each other.

“As a society, we’ve made these silos because if we can say that there’s one root cause, then there’s one answer,” says Turner. “And as a result, everyone points to an explanation based on their world view and says, ‘if we can fix this, we’d be okay.’ But that’s not how society works.”

Politics, too, are part of how society works. In November, Pennsylvanians will vote not only in the midterm elections at the national level but also to determine whether Governor Wolf receives a second term. Wolf, who is generally regarded as one of the most liberal governors in the country, is running for reelection in a state that in 2016, swung for the Republican presidential candidate for the first time in nearly 30 years. The Center of Excellence grant, among many other opioid-related programs, was instituted by Wolf’s administration and therefore may lack the staying power of legislature-driven policies. Steiner, among others, shared the concern that if Wolf loses the election and programs are revoked, it’s the people who benefit from these new services that will suffer most.

“I’m very concerned that we might lose the third year of the grant’s funding,” says Steiner. “Having this grant gives us more autonomy to be creative in how we engage our clients — some of our services are a little unorthodox, but it’s working. We’re doing what we need to do to serve our community and those in need. It’s been a blessing for us.”

When a problem becomes an epidemic

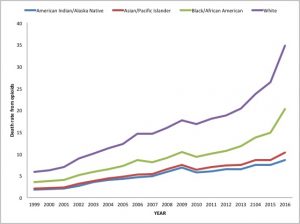

The opioid epidemic is often presented as a problem that only affects poor, working-class white communities, but recent trends suggest otherwise.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data presented in the above chart reveals that death rates are rising most steeply amongst minority communities. In November, the Chicago Urban League produced a report excoriating the federal government, as well as the country as a whole, for ignoring how the epidemic has affected urban black communities. According to the report, black people account for more than half of the city’s opioid-related deaths despite accounting for less than a third of the population.

And in Allentown, a majority-minority city, local experts are also trying to change the perception.

“People need to open their eyes because this epidemic is affecting everyone: rich people, poor people, every race and ethnicity,” says Michelle Steiner, the care manager and program director of the Center of Excellence, an addiction treatment center in downtown Allentown. “It’s not just the individual under the bridge anymore.” –GK

Gregory Kantor served as the Editor-in-Chief from 2016 -2018 and majored in Public Health with a minor in Jewish Studies. In addition to his work with The Weekly, Greg served on Muhlenberg College EMS and worked in the Writing Center. A native Long Islander, he enjoys watching New York's losing teams – the Mets, Jets, and Islanders – in his free time.