Sergeant David Emme was in a supply truck when the IUD exploded. “I didn’t know who I was when I woke up,” he said. “I wanted to die to get rid of the pain.”

Traveling in a convoy in Iraq, Emme’s assignment was still considered a combat attack since they had the possibility of falling under attack. The truck was en route when Emme noticed teenage boys beside the road.

“They were giving us cut-throat signs,” he said. “They were warning us.”

They barely had time to react. The explosion happened near the vehicle. The driver of the truck ignored his wounds in order to bandage Emme, who was pulled out the truck to safety. Shrapnel embedded into his brain required removal of a large piece of his skull. He lay in a coma for days following the attack. The headaches are a physical reminder. The emotional scars are another thing entirely.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has only recently been recognized as a psychiatric issue since the rise of psychology and neurology studies. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), a handbook used by healthcare professionals, defines PTSD as “exposure to a traumatic event that meets specific stipulations and symptoms from each of four symptom clusters: intrusion, avoidance, negative alterations in cognitions and mood, and alterations in arousal and reactivity.” It emerged during World War I at a time when no clinical terms were used to describe mental distress. Instead, stigmatizing labels were cast on soldiers who experienced emotional suffering.

“Soldiers were reluctant to admit to mental distress,” said Dr. Dan Wilson, professor of history at Muhlenberg.

Servicemen were soon diagnosed with “shell shock.” Aside from the physical injuries of an explosion, they experienced amnesia, paralysis, and deafness. As the United States partook in more wars, different definitions were used to explain the same symptoms: war neurosis, exhaustion. Psychologists struggled to diagnose soldiers in fear they were malingering, or exaggerating illness to avoid the war.

“There were no organic manifestations,” Wilson said. “[Many] doctors held the same stance: If there was no physical wound, the soldier suffered from cowardice or malingering.”

With more soldiers falling ill to this mysterious disorder, a common goal emerged among military administration: get soldiers back to their unit as quickly as possible. It was more important to have men on the line than to figure out the plague that was sweeping across every branch of the military.

Major Nathan Kline of the Air Force, and a Muhlenberg alumnus, knows firsthand the stress of war. He flew 65 missions during World War II as a bombardier-navigator, and was shot down twice in the span of a week.

“I wasn’t [even] 21 when I flew as a bombardier in Europe,” Kline said.

After being shot down, Kline was sent to a rest home in England.

“The day before I returned [to duty], the crew I had flown with for the last twelve years was shot down and all killed. I should have been on that mission.”

After returning home from the war, Kline started to experience PTSD symptoms. He was admitted to the hospital for months. When he looked in the mirror, he couldn’t recognize himself.

“My eyes were like red coals,” he said.

Kline found solace talking with other patients. He could relate to what they were going through. It became clear that every returning soldier struggled with similar baggage.

“When I was in that coma, I felt like I was in hell.” Emme described the pain after his attack as unbearable, like his head was on fire. Emme is afraid to fall asleep every night because it feels like a shock wave is going off.

For Kline, it was similar.

“I would do crazy things in my sleep,” he said. “When I’m under stress, it really comes back. It’s hard to explain how it feels. It’s something I will never forget.”

As long as the military exists, so will PTSD and other mental illnesses. Young men and women are not only signing up for promises of heroism, but emotional distress as well. Open dialogue on mental illness has brought attention to the invisible wounds, but what’s more important is talking about what can be done.

For Senior Master Sergeant Jeff Capwell, meeting with other veterans helps manage his wellbeing.

“I can go in there and walk out feeling better,” he said. “We get strength from each other.”

For Emme, that meant working towards a degree from the Wescoe School despite headaches that left him disabled for months and made completing school work impossible.

“You could see at certain points he would struggle,” said Joe Kornfeind, Associate Dean of the Wescoe School, who had Emme in his leadership class. “He had one paper to hand in to earn his degree and he couldn’t hand it in. It took a year until he was able to.”

Despite the damage Emme experienced emotionally and physically, he found the perseverance to keep moving forward. When he handed in the final paper, Kornfeind was astounded. Emme’s paper included a learning model of what he himself did when his PTSD became overwhelming.

“It was one of the best papers I ever read.”

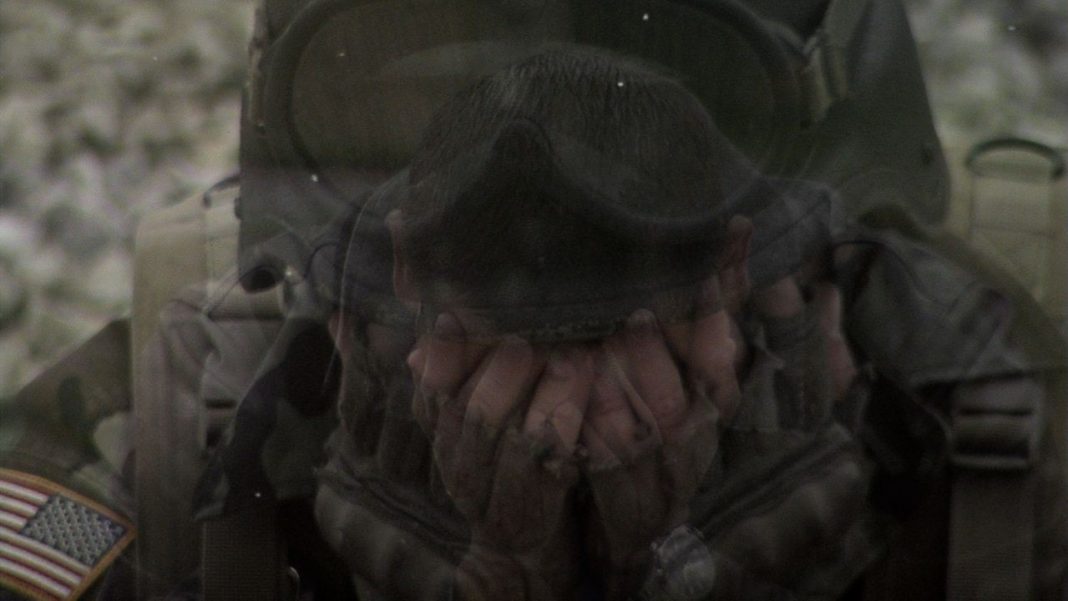

Photo Credit: “Regret” by Peter Murphy, unedited; CC BY-ND 2.0