When choosing to purchase a house, there are plenty of factors to be considered. For many, an important element is the quality of the local public schools. In modern day America, systems of housing and education are inextricably linked to one another. In addition to paying your mortgage, homeowners also pay property taxes that fund public schools in their city, which has major consequences for various neighborhoods based on the socioeconomic status of individuals living there. This rings true for the Lehigh Valley, and the Allentown School District (ASD) in particular.

An important factor to consider when thinking about the connection between taxes and school funding is the practice of redlining. Karen Pooley, Ph.D., a professor of practice in the department of political science at Lehigh University and former executive director of the Redevelopment Authority of the City of Allentown from 2007 to 2011, teaches courses on city planning, neighborhood and housing issues. Pooley explains that the practice of redlining emerged in the 1930s, and was based on stereotypes of immigrant communities and communities of color that were imposed by banks.

“[Banks] didn’t think really highly of anybody who was on the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder,” she explains. “So if it’s a neighborhood that’s occupied by immigrants or working class [people], or non-white households, the expectation was the neighborhood was on the verge of falling apart, hazardous for future investment. And so these maps very much showed where older housing, where denser housing, where lower income, lower socioeconomic status households are living.”

To identify the places where banks, insurers and the government wanted to avoid investing any money in, maps were created with lines drawn in red to warn against neighborhoods which investors considered hazardous—this is what we now know as redlining.

“When it came time to figure out where are we going to invest, where are we not going to invest, where are we going to encourage homeowners to buy new houses, where are we going to encourage builders to build, we’re not going to do that in these areas that we’ve designated as hazardous for future investment,” explains Pooley.

“So the act of redlining is ‘we’re going to avoid investing in certain areas.'”

Karen Pooley

Allentown doesn’t have a redlining map, or at least not one that has survived to be examined today. Yet, even without an official red line on a map, investors seem to have drawn that line of their own when it comes to home sales in the city.

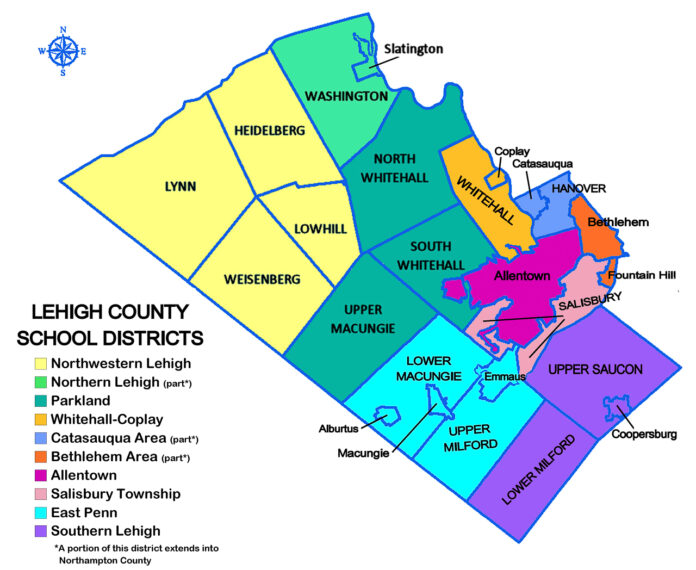

“If you look at the school district boundaries, [in] other districts in the county, they’re squares, they’re rectangles,” explains James Wynne ‘23, a 2019 graduate of William Allen High School and current Muhlenberg student who says that this invisible redlining impacted his school district. “[For] Allentown School District, it looks like something you’d see in biology class. It’s ridiculous. And most of that are dilapidated communities with houses and buildings with low property value. And so if you just think about it mathematically, lower quality housing, you’re going to have lower property taxes.”

Pooley summarizes redlining as “disinvesting in denser, more diverse, older places,” a description which aptly fits Allentown.

The existence of the redline has dire consequences on school districts around the country which depend on property taxes for funding.

“If you’re in an area that has property values that are lower,” explains Nick Miller, an Allentown School Board former vice president and current member, “such as in Allentown versus Parkland, where [there are] nicer houses and the property value is a lot higher, you can tax that at a lower percentage of the higher value property. Whereas in Allentown, the property value is $80,000 and you’re still taxing it at five percent, that five percent on $300,000 is a lot more. So that’s where the disadvantage is, especially with a full tax base that’s, on average, lower… It’s across the state that in urban districts that have that issue.”

“In most cases, where you live determines where you go to school,” explains Pooley. “And you don’t get to just show up in a neighborhood and say ‘this school is fabulous, yes, I’d like to go to this one,’ you need to show an electric bill and you need to have proof of residency in that district in order to be able to go. The primary way schools raise money for the things that they do, for the teachers that they pay, and the books that they buy and after school programming, and everything that they do is primarily from real estate tax. So not only do humans have to live in a house to go to a school, but the school gets their revenue primarily from the value of the real estate in that place. So when it works, it works… Where it doesn’t work it’s horrible. So then you have not enough resources to support your schools, schools suffer because [you’ve] got to cut out any of the extras like art or music or things that kids desperately need. Or, not hire enough staff and all of a sudden classes get a little bigger.”

“demand for housing in that district starts to go down because people want to move to where there’s a stronger school.”

Karen Pooley

The relationship between property taxes and school funding creates a vicious cycle where wealthier people tend to want to live in these cities, which brings in more of their money.

“School districts with higher property values have more [money] to spend,” explains Michele Moser Deegan, Ph.D., dean of academic life and professor of political science at Muhlenberg College. “And, districts like Parkland and Emmaus have large education funds and booster clubs that support the extracurriculars that Allentown parents can’t afford. The out-of-pocket differences are noticeable if you go to a sporting event or even a theater production. Non-profit foundations do try and help but in the Lehigh Valley, we don’t have a lot of really rich people to give the funds needed to the district and they tend to give to their home district, which is more likely Parkland, Emmaus or Southern Lehigh.”

According to the Lehigh Valley Planning Commission, the Allentown School District median household income is $39,820, a vastly different number than the Parkland School District’s median household income of $84,646. This discrepancy in income is what leads to the discrepancy in availability of resources and extracurriculars in the two school districts.

Additionally, 4.5/10 households in Allentown are cost-burdened (meaning more than 30% of one’s income pays for housing) while 2.6/10 households in the Parkland area are cost-burdened. These numbers demonstrate a significantly greater density of wealth in the Parkland area, and illustrate that there is more loose money to provide more adequate resources to the schools there.

“When you’ve got really high value housing,” says Pooley. “You’ve got a lot of money to support really high quality schools, which only further increases the value of that housing because everybody wants to get in to attend those schools.”

Ultimately, students in the Allentown School District suffer the consequences of politics that are far beyond their control. The historic and contemporary practice of redlining has led to a cycle of generational harm for those who are unable to access the same resources as their neighbors who live mere miles away.

This was originally published in the Allentown Voice, a student journalism lab covering housing in Allentown.

Cydney Wilson ’23 is a Political Science major with a self-design major in Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies and a minor in Africana Studies. Being The Weekly’s editor-in-chief has been one of the greatest joys of her college experience. She enjoys writing about the subjects that make people angry, and hopes that her journalism will inspire change, both on campus and in the world.