It was a hot and sticky day, typical of the valley in July, and Mike Donnelly sat in his office rearranging the possible offensive and defensive lines he’d use during preseason. He’d started off the day sitting on one of the recumbent bikes in the cardio loft, reading a history book, as so many had seen him do. Now he talked about his sport and seconds into the interview he was detailing each player’s contribution to the team, the pride in his recruits shining through.

And then he began to discuss another game — a battle in hospitals rather than on the gridiron.

He unabashedly delved into the details of his treatment while tucking his catheter into a white bandage hidden under his shirt.

“They give you your numbers,” said Donnelly. “It becomes a game. So for example, this is my hemoglobin and those are the reference numbers. If it’s low and they tell me I need a transfusion for something, five hours. If not, you walk right out.”

He analyzed each number like he had his players minutes before. Everything he said led back to football, the thing he knew best and what got him through his trips to Roswell Park Cancer Institute in Buffalo, N.Y.

Donnelly, who most people called Duke, died on Oct. 4 of complications from his battle with acute monocytic leukemia. He is survived by his wife, Beth, and children, Lauren and Brendan. He was 65 years old.

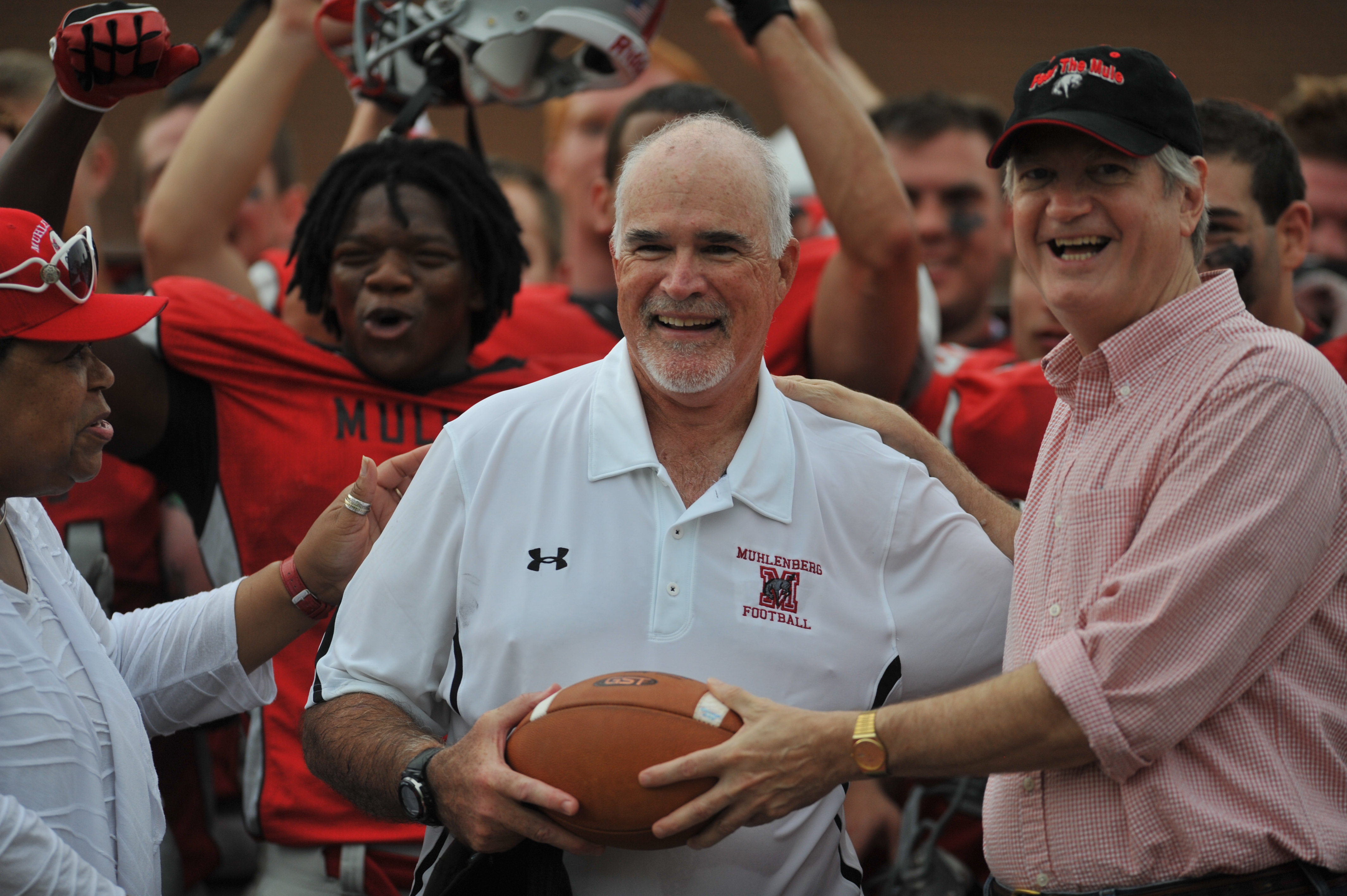

Two weeks ago, just days after learning of their head coach’s passing, the one hundred players that make up Muhlenberg’s football team made the decision to play, because that’s what he would’ve wanted. The team wanted to win all its games for the winningest coach in Muhlenberg history, but, with the realization that he would not return to the sideline, the sense of urgency was greater. So they did what their coach had taught them — dig in, find a way to win. And they did, beating the undefeated Ursinus College Bears 21-14. One more win to add to his record.

Winning wasn’t everything to Mike “Duke” Donnelly.

But football was.

One visit to his office would prove that. On his shelves sat predictable items of sentimental value to a football coach: a watch sitting in a cushioned box labeled “there’s no substitute for victory,” his first Muhlenberg career win ball balanced next to his 100th win ball and, proudly displayed at center, his first shutout football. A trophy nearly as tall as his desk gathers dust on the floor. Hanging above the magnetic board that displays the names of each of his players are drawings given to Donnelly by different children, his own family and fans of the program. The ledge of the window overlooking Frank Marino Field is lined with plaques and pictures. All of it, one way or another, highlights some memorable moment of his 21 years at Muhlenberg and 41 years as a coach.

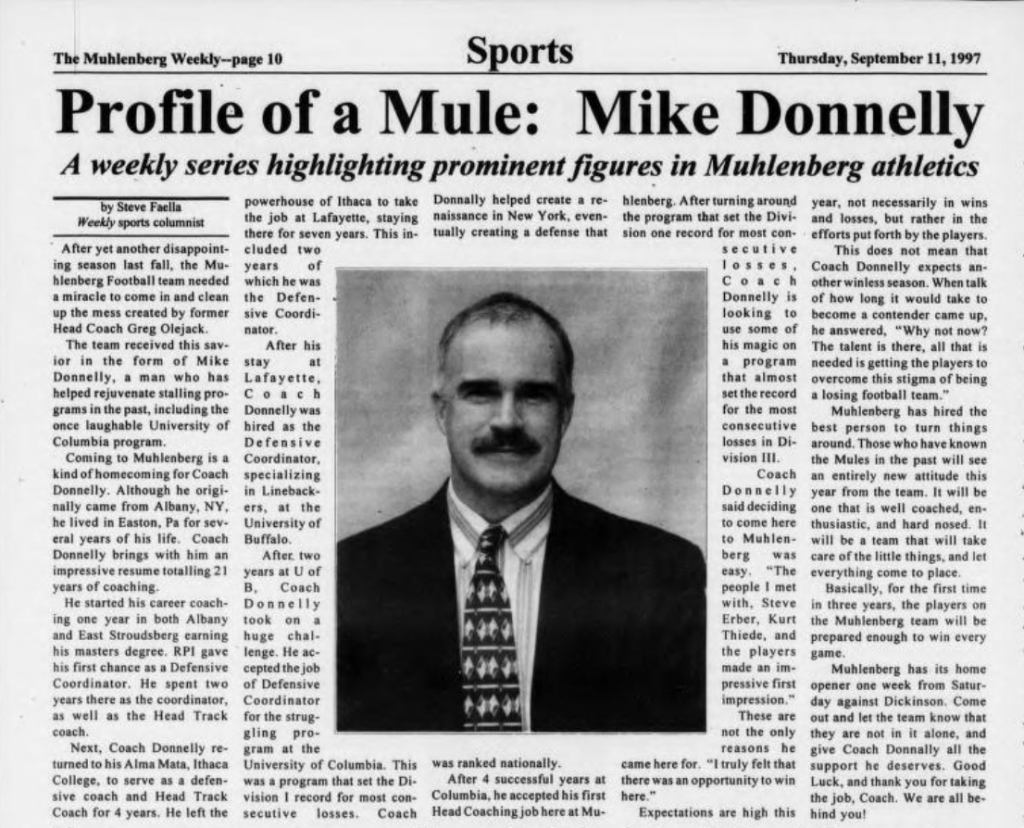

Donnelly’s career ranged from high school to Division I programs. He coached at Albany, East Stroudsburg, Rensselaer, Ithaca, Lafayette, Buffalo and Columbia. While he was not always the head man, success followed him wherever he went. As a defensive coordinator and linebackers coach, Donnelly led Columbia’s defense to national prominence in 1996, producing three first team all-Ivy players, ranking in the top 20 in seven defensive categories and sending defensive end Marcellus Wiley to the National Football League.

Duke left an impression everywhere he went.

“We lost a good friend, man and husband, a great football coach,” said Denny Douds, head coach at East Stroudsburg University. “He made significant contributions, especially at Muhlenberg where he ran a top shelf program.”

Winning wasn’t everything to Mike “Duke” Donnelly.

But football was.

This sentiment – that the football world and Muhlenberg community had lost not just an extraordinary head coach but an even better human being – echoed throughout campus and the football world.

“He was just super passionate and had a way of making you feel important, whether you were an All-American or never played a down,” said assistant coach and alum Josh Carter ‘01. “He thought everybody had an important role. And that’s how he went about life. From Plant Ops all the way to the president, for the Muhlenberg football program to be successful, he needed those relationships.”

After spending half his career moving from school to school, always in search of another place he could make his mark, Donnelly found a home at Muhlenberg. The head coach headset was handed over in 1997 and with it went the losing epidemic. When he took over, Muhlenberg had won just three games in three years. Donnelly resurrected the floundering program, turned Muhlenberg into a perennial powerhouse, a nationally ranked top-10 team, and led the Mules to the ECAC Southwest championship just four years after his arrival.

Under Donnelly, Muhlenberg football had few unsuccessful seasons: 13 postseason berths since 2000, making their first national playoff appearance in 2002, tying for the Centennial Conference championship in four straight years from 2001-04, win after win after win.

He led Muhlenberg to a 6-4 finish and its first winning record in 10 years in 1999.

Just one year later, he sent the Mules to their first postseason appearance since 1946.

Donnelly earned the title of Regional Coach of the Year by the American Football Coaches Association after leading the Mules to their first undefeated regular season in the 106-year history of the program; Muhlenberg would go on to win the Centennial Conference championship and advance to the second round of the NCAA Division III playoffs. The next year, after winning the CC championship again, he was voted CC Coach of the Year.

He coached 19 All-Americans, nine Centennial Conference players of the year, two CC rookies of the year and the program’s all-time leaders in almost every statistical category.

Only one coach in the Centennial Conference has more championships than Donnelly’s seven.

It’s evident that Mike Donnelly was no ordinary football coach. But what made Duke so successful?

Athletic director and acting head coach Corey Goff said, “The wins and losses are important to his legacy. It’s a byproduct of who he was but it’s not the punchline.”

Donnelly had a life off the football field that seemed, in so many ways, to inform his abilities as a coach.

He was a history buff. Donnelly could often be found on a recumbent bike reading a book about World War II and be fascinated in the details. He’d catch you in the hallway and want to talk about the interesting nuances of WWII fighter planes. He told his players about new books he’d read and the lessons that they could take away from historical events.

He was fascinated with cars and his beloved Porsche.

He was described as incredibly intelligent, a lifelong learner.

He stood up for what he believed in, which included punching a classmate in the nose as a final resort to keep him from driving drunk.

He enjoyed Diners, Driveins and Dives, cigars and a glass of scotch.

He had stories for days and you’d never hear the story just once.

He had infectious smile and an unmatched sense of humor. Greg Mitton, a long time friend and the voice of Muhlenberg football reminisced about one of Donnelly’s classics, where he would ask someone “Do you know who’s looking for you?” to which they would respond “Who?” and he would laugh and say “Absolutely nobody.”

He was incredibly stubborn – you could say, as a mule – mostly when it counted.

“He taught young men to be advocates for what they believe in, for what they think is right,” Goff said. “He’s always been known as a professional arguer. He’ll talk for three hours about the minutest of details just to make sure that you fully understand what you’re arguing for.”

But sometimes when it didn’t count. As John Loose, an assistant coach at the United States Military Academy West Point, recalled, he’d received butt-dials recently from Donnelly on more than one occasion where he could hear Duke arguing with the nurses about what they were doing wrong.

Donnelly had a life off the football field that seemed, in so many ways, to inform his abilities as a coach.

He had an impressive collection of Hawaiian shirts. “My two favorites were his ‘Day of the Dead’ one and the one that had different models of old airplanes flying on it,” remembered Luke Wiley ‘19. “If he saw someone in a Hawaiian shirt one day, you could expect to see him in one of his within the week.”He appreciated details.

He valued education, asking for Muhlenberg’s Trexler Library to be open in the summer when his recruits came to campus.

He had a larger than life personality.

“On my very first day practicing, Coach had myself and several other freshman returning punts,” recounted Matthew Stickney ‘18. “After a couple went uncaught and we were ‘commanded’ to not let another touch the ground, the next punt fell right between another teammate and myself. I turned and looked at my teammate and then at Coach who yelled, ‘28, you have got to be the dumbest freshman I have ever recruited.’ After a couple weeks, I realized every freshman is the dumbest freshman Coach has ever recruited.”

“Duke had an adaptive philosophy. He was a little bit old school, little bit new school. His relationships with the players were new school,” said Tim Moncman, Parkland High School coach and one of Donnelly’s former players. “He was your coach, but he also saw the human being side of you. Most old school coaches back then didn’t do that. He cared about you.”

Mike Donnelly cared about people and people cared about him, as was evident by the crowd that filled the seats and corridors of Muhlenberg’s Egner Memorial Chapel and Miller Forum, which provided overflow seating. With his current 100 players and coaching staff in front, former players, parents, students, Muhlenberg staff, friends and coaches from seemingly everywhere sat in melancholy silence to celebrate the life of one of Muhlenberg’s greatest.

“Mike is one of those special people that was not just a colleague, not just a friend, but family,” said Mitton. “He’s one of those individuals that you don’t tell them enough how much they mean to you personally, or how much he meant to this institution. There’s a certain attitude that Muhlenberg kids have – they’re kind, they’re genuine, they’re really hard working, ultimately put others before themselves. I think Mike was a Muhlenberg kid, more a Muhlenberg person. He really did care about this place. He loved this place. Yeah he won a lot of football games and he cared about the men on that team, but he cared just as much about the rest of the community.”

Stickney and George DiFiore ‘18, like so many who shared their fondness for Donnelly, spoke highly of what their coach had done for them both on the field and in life. For them, the Duke was a great coach and even better man who taught them how to become better football players but even better people. He got so much joy out of showing guys there’s more to life than simply the Xs and Os of the game.

“Coach treated us like men on the football field,” said Stickney. “But, what I loved most about him, was how he treated us off the field. We were one of his sons.”

For Donnelly, a man described as humble and more invested in those around him than himself, those same qualities that made him a great coach were only more apparent after his diagnosis. He knew how to play the game. He knew how to coach. He knew how to mentor. He knew the importance of being a leader. Through treatment, he was focused on his team and their continued success, with or without him.

“I worry about our kids. No matter what happens to me, I want every one of my kids to get their degree and I want them to have a great football season this fall,” said Donnelly in an interview shortly before going to New York for treatment.

He reviewed practice and game tape from his hospital room and kept in constant contact with his coaching staff. He actively watched the live stream of every football game as it unfolded. He ensured that the donuts he brought for his team every Wednesday kept showing up, even from hundreds of miles away, because it was something his players had grown accustomed to. Every step of the way, he put his team before his diagnosis.

In the months following his diagnosis, Donnelly’s strong advocacy for leukemia awareness added yet another thing to his legacy. He began to promote and support “Be the Match” and the Andy Talley Bone Marrow Foundation. Muhlenberg football and the community spearheaded the Dig In for Duke campaign, including a day-long campus blood and bone marrow registry drive in September. Almost 400 new marrow registry signups and about 59 blood donations came from that event, aptly called “Muhlenberg Gives.”

He got so much joy out of showing guys there’s more to life than simply the Xs and Os of the game.

That is something he would’ve wanted to be remembered for. His legacy, his personality, his impact will live on.

“He’s going to be missed,” said Carter. “Sometimes it’s hard to pinpoint all the different ways but, with him, you can just know.”

Muhlenberg’s football program would not be what it is today without Donnelly. Neither would a college community that, for many years on, will hear echoes of the Duke’s deep voice, arguing, joking and telling stories and making things just a little bit brighter.

Additional Reporting by Matt Riebesell.

Alyssa Hertel was the Managing Editor of The Muhlenberg Weekly. She graduated with a degree in Media & Communication with double minors in Creative Writing and International Relations. An avid fan of perfectly average sports teams, she is pursuing a career in journalism focusing in sports.