In the light of this week’s Black Lives Matter speaker, it is important to look back at similar speeches that have come before. Though many believe Black Lives Matter is a new movement, its roots spread back farther than imagined. The adage that history repeats itself is one I’ve never given much credit to, but this week’s speech gave some credence to it.

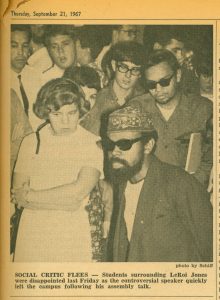

Almost exactly 50 years ago today, Amiri Baraka, formerly LeRoi Jones, noted civil rights activist, spoke at Muhlenberg College.

Amiri Baraka, born LeRoi Jones, was a poet, writer, actor, director, and a devout activist for social justice and African American rights. After the assassination of Malcolm X in 1965, Baraka changed his name from Everett LeRoi Jones to Amiri Baraka. At his time during the racial unrest of the civil rights era, many saw his ideas as more “radical” and “provocative” than most. However that did not stop him from speaking at Muhlenberg College to a crowd of 1,800 people. It is important to note that college enrollment at the time was around 1,500, so his reach far exceeded that of Muhlenberg’s campus.

The headline of the September 21, 1967 Weekly sets the tone for Baraka’s speech: “LeRoi Jones stuns Whitey: ‘Black power will prevail’.” The Weekly describes Baraka as, according to the “White Man’s eyes,” “a militant, trouble-stirring-upper Negro, from whose lips the phrase ‘black power’ is never long absent.” Baraka began his speech reading an excerpt from an essay he was trying to get published, but remarked likely wouldn’t due to its content. The essay, mirroring modern sentiments, spoke on the “civic corruption” of Newark. Baraka spoke on the mafia stronghold over the city, and their absolute disenfranchisement of the “Newark Negroes” who made up over 50% of the city’s population. He also spoke on the ongoing riots, and the tokenism of black police officers. Baraka argued that not only were no black policemen above the rank of lieutenant, but that any police officer promoted close was done so to advance the claims of “Great Strides Forward” the white liberals were pushing. Baraka claimed that though his “black brethren” were approaching some level of freedom, those at the top were still forced “to eat the same amount of shit they ever did.”

His speech hit a climax when Braka called for the creation of a “Negro State.” He felt this would end the strife of the ongoing riots and cause peace between the now separated races. Baraka felt this would be a very easy change; simply using the already present separatism now to their advantage. He called this process “natural and irrevocable,” and went on to call for the “collectivization of Negro force for the Big Put-Down of the White Man.” Calling his language “downright offensive to our white (lily-white) ears,” the Weekly went on to say Baraka was “in short, no joy to hear.” Admitting their own bias, the article wraps up, “we, who represent for the most part, the white middle-class, whose rights and freedom go unquestioned, are not the ones in the slums, waiting and rotting while we wait. Until we have some answers, some solutions, we whites would like the blacks to wait some more — but, as ever, we would be comfortably resting on top of them.”

In the same issue, a letter to the editor entitled “People Power” draws clear parallels to today’s notion that “all lives matter.” In the letter, the writer, who requested to remain anonymous, wrote that the cry of “black power” was “very shallow” and done so in vain. The writer goes on to claim that both sides should come together to fight, not the white man, but instead the “white Establishment.” They end their letter claiming that “a real social critic doesn’t cry for ‘black power’ nor for ‘white power,’ but for ‘people power’.” Though some contemporary and modern advocated for social justice may have seen Baraka’s cries for black power as different from their own, the silencing of such cries to instead be lumped in with the empowerment of whites draws clear ties to today’s ill-conceived “all lives matter” movement.

Unsurprisingly, Baraka’s speech was not greeted with total approval. Articles such as “College image suffers in LeRoi Jones aftermath” go on to explain that the greater Allentown area condemned the college’s allowance of such a vulgar speech. The Call-Chronicle even published an article titled “Was All the Filth Necessary?” in which they implied that Baraka was met with resounding support after his speech. In her letter to the editor, then sophomore Debbie Burin ‘79 debunked this assumption, while also criticizing their “most un-American attitude.” Burin admits that those in full support of Baraka were in the vast minority, but still believed that the students had every right to hear him speak. Burin writes, “How can these citizens claim to have an All-American city when they seem to want to have a ‘Big Brother’ of Orwell’s 1984 watching over the young people of today making sure they hear only what the citizens consider worth reading or hearing?” Burin ends her letter saying that she is “still proud to be a student of Muhlenberg College for here we are permitted to get first-hand knowledge.”

With the ill-will towards the college continuing, then president Erling Jensen published a statement in the October 12, 1967 issue of The Weekly. In it he wrote:

The students on college campuses, including those at Muhlenberg College, must be able to hear about, and discuss, these important issues that are of such great concern throughout the entire country… Our students must be acquainted with these problems, since they are the ones who will be participating in the decisions and the proposed solutions that hopefully will solve this very serious problem.

Jensen stressed the importance of student expression and their ability to choose their own speakers. For this, rumors of his forced resignation at the hand of the Board of Trustees circulated, and student protest erupted in support of their free-speaking president.

Though this week’s speech was met with some backlash, both online and in person, it still had a clear and important message. Though not the same as Baraka’s, the stories of riots between police and innocent people of color as well as a country seemingly led with white interests solely in thought were preached by both speakers. One could argue these two speeches a half century apart are an example of history repeating itself, but instead I ask you to think of these speeches as not two disconnected events, but instead one voice left unanswered for so long.