Students who love, or don’t love, Shakespeare had the opportunity to attend the 35th Annual John D. M. Brown lecture and hear a refreshing take on “Othello.”

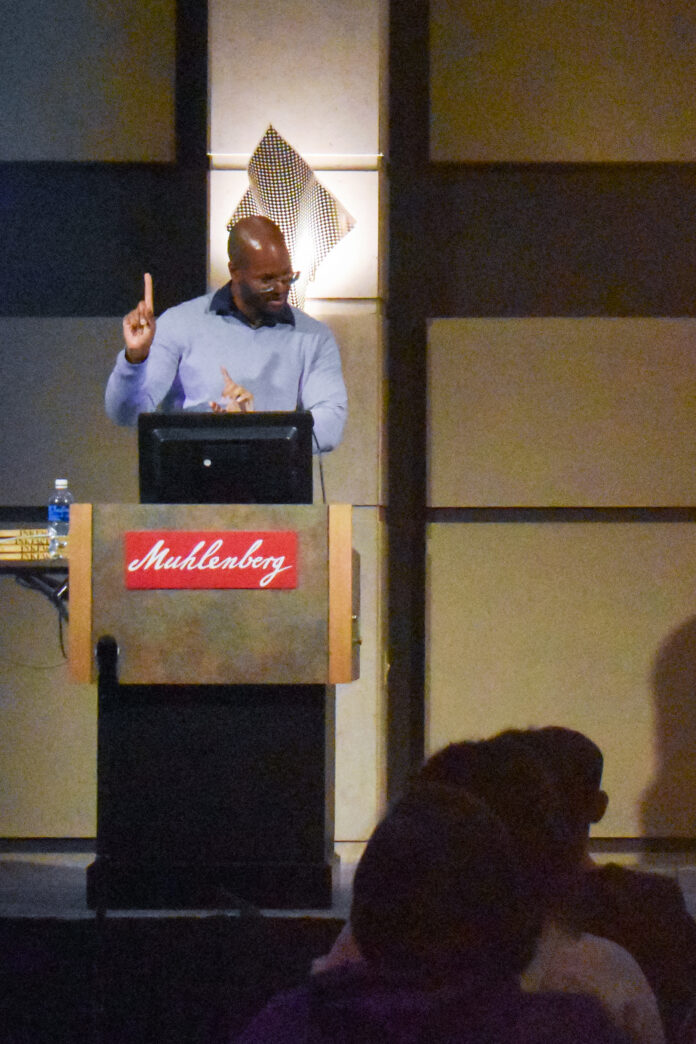

The John D. M. Brown lecture series, held in memory of the alumnus who graduated in 1906 and former Muhlenberg English professor, has been going on since 1987, with a two-year break due to the pandemic. Past speakers have come from all over America and the UK. This year’s lecture was given by Miles Grier, Ph.D., on Feb. 29 in the Miller Forum. According to his biography in the program, Grier “is an associate professor of English at Queens College and the Graduate Center, CUNY.” His book “lnkface: Othello and White Authority in the Era of Atlantic Slavery,” from which his lecture was derived, was published last year.

Before attendees went in for the lecture, some students explained why they were attending. The rhetoric included how the lecture sounded really cool and a love for “Othello,” plus, extra credit. One attendee Beck Mann ‘27, who was also an “Othello” lover, added, “I don’t get extra credit for this, so I’m just here for fun.”

Ana Erickson ‘25 gave her insight on how she felt before the talk, saying, “I had to read some of his writing for my “Othello” class and it was really thought-provoking, so I went into the talk feeling super excited to see how he would elaborate all of that.”

At 7 p.m., students and community members gathered into Miller Forum.

To the tune of crinkling popcorn bags–snacks had been served beforehand, Grier began his lecture with a question to the audience: “How would you describe the shape of racism in America after the Obama presidency?” Several people gave some answers which offered various perspectives. The consensus seemed to be that racism didn’t disappear once America had a Black president, because racism is interpersonal but also systematic. Grier seconded this interpretation and added his own thoughts, claiming that the character people are supposed to aspire to have is a standard created by white men. That is, forcing people of color to defy stereotypes to be considered worthy of society’s praise is just as problematic as overt racist actions. He then took the word “character” and used its multiple definitions—the quality of a person versus a letter on the page—to pivot to his discussion of “Othello.”

“Othello” is a play about “a marriage between the exotic Moor Othello and the Venetian lady Desdemona that begins with elopement and mutual devotion, and ends with jealous rage and death,” according to the Folger Shakespeare Library. The term “Moor” was used in Shakespeare’s time to refer to the inhabitants of North Africa. To put it simply, this play is about an interracial marriage that cannot survive the pressures of the society in which it exists.

Throughout his lecture, Grier explored the interweaving of Black people and ink, both in the play and in the wider world around Shakespeare’s time. For example, he pointed out that Othello’s suicide note is punctuated with the line “O bloody period.” He used this example to claim that, in a way, Othello “bleeds ink.” The next section of the lecture answered a question that some audience members didn’t think to answer: why does Othello “bleed ink?” Why does Shakespeare use that particular image? The answer, according to Grier, lies in the view that Europeans had of Africans at the time of this play’s publication. Many people in Africa had tattoos that denoted their rank in society, and before the standardization of English spelling, “race” was a word that could be used to refer to a person’s skin, but also body markings or tattoos. As such, he argued, ink was intertwined with the European view of Black people at this time.

Anna Hanley ‘25 said, “We had a really in-depth conversation around the staging of ‘Othello’ and how it should be done as well as what purpose this show in our modern day society is serving and who is benefiting from it.”

Grier’s other significant point lies in the way Othello seems to doom Desdemona simply by being in a relationship with her. For hundreds of years, productions of “Othello” would have a white man playing the titular role with paint covering his body. Before Othello kills Desdemona, he kisses her, and in those productions, some paint rubs off on her. Grier distinguished this from what we typically think of as blackface because of that transfer. This is what he referred to as “Inkface,” a Black character who “meets writing with the body,” “bears dishonorable slave stigma” and, importantly, “transfers that stigma to partners and children.”

He left the audience with this question: who has the power to decide who is marked and what those markings mean?

After the lecture, there was a short Q&A session. Once that was over, The Weekly approached Grier to ask him what it was like to give a John D.M. Brown lecture. He mentioned how “It is really an honor” and that “The people who preceded me I looked up to for years.” And it seemed he enjoyed the audience just as much as they enjoyed him, calling the room “vibrant and smart.”

“I thought that his answers were very thoughtful and I appreciated how he asked audience members to ask questions first. It made the space feel much more engaging and welcoming than other talks that I’ve been to,” Erickson concluded.