If you drive around the city of Allentown, you may notice a distinct lack of ‘for sale’ or ‘for rent’ signs. For a city that has spent several million dollars on revitalization, they are now facing a new problem–there isn’t enough housing for the number of people who want to live here. More importantly, there isn’t enough affordable housing.

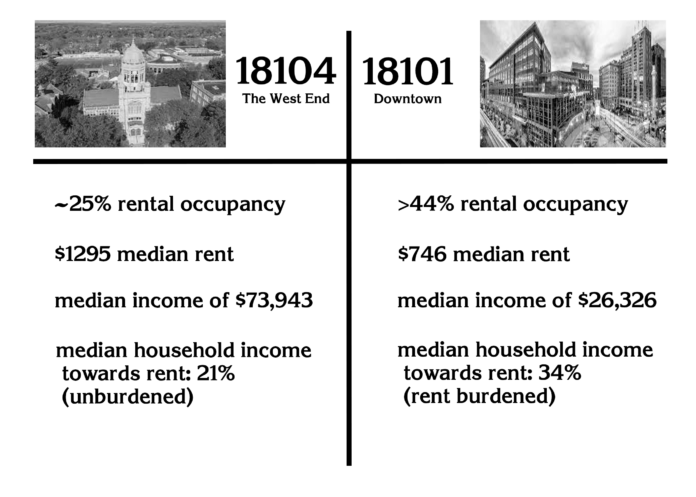

In Allentown, an estimated 54.7 percent of renters pay more than 30 percent of their income towards rent, qualifying more than half of Allentown’s population as rent-burdened by Census standards. As of 2019, the median gross rent in Allentown was $1,004 monthly. The median household income was $41,167, meaning the median household falls barely under being rent burdened, at 29.2 percent of pre-tax income put towards rent. Simply, there aren’t enough units to house everyone, so rents keep going up.

Tim Ramos, the Republican nominee in the Allentown mayoral race, says, “The crisis in affordable housing is hitting our communities hard. We’ve seen rent go up by hundreds of dollars just since the pandemic, and it’s reaching the point that long-term residents are struggling to stay.”

The crisis in affordable housing is hitting our communities hard. We’ve seen rent go up by hundreds of dollars just since the pandemic, and it’s reaching the point that long-term residents are struggling to stay.

Tim Ramos

The housing crisis doesn’t just look like expensive rents, it also has to do with what one scholar calls the “geography of opportunity.”

“It’s the housing package; all the stuff that comes with your house,” explains Karen Pooley, professor of political science at Lehigh University, focusing on urban development. “It’s the stuff on the inside. You have two or three bathrooms, but then it’s also all that stuff that’s on the outside. So parks and grocery stores and transit and good schools and those kinds of things. And your pathway to that stuff is through the housing that’s near that stuff.”

And constructing new housing isn’t a sure solution. “Housing takes a lot of time to build,” explains Pooley, “so if you have a lot of people who want it, it’s going to take a while for the supply to ratchet up.”

Zoning laws are the means with which cities can control how land is used—but these laws can also be hard to change. “From my perspective,” says Cristian deRitis, deputy chief economist at Moody’s Analytics, “a lot of this comes down to zoning; changing zoning requirements, increasing the density in some of these areas. We have many communities where, for example, you are only allowed to build one single family home on a lot. Clearly given the demand for certain areas, particularly suburban types of areas, that’s insufficient.”

Adding to the difficulty of changing zoning laws is battling the problem of NIMBYism, or “Not In My BackYard.” “What you often have are communities that are with an idea in spirit,” says deRitis. “Everyone’s on board with that until you tell them that it’s their neighborhood, or it’s their property that we’re talking about.”

Pooley connects this NIMBYism to the history of redlining in America, a policy by which neighborhoods where Black residents lived were deemed as too “risky” for federally subsidized mortgages, leading to lower rates of Black homeownership and less ability to accrue generational wealth. “If you’ve seen any of those redlining maps, a lot of the redlined areas were places that had denser housing that you had in the 1930s, and the more integrated the neighborhood in terms of income, certainly in terms of race, the lower your rating was going to be on those maps. [With denser, more integrated housing,] you’re going to be in the yellow or the red zone. [Even today,] if an apartment complex is proposed in a neighborhood that doesn’t have a lot of dense housing in 2021, that community meeting will erupt.”

“You do see a number of communities pushing back against these efforts to increase or change zoning rules, because it might change the character of their neighborhood, might change just what they’re used to. It certainly will bring more individuals to the area so there are concerns about traffic as well, local traffic at least. So it’s not an easy issue,” says deRitis. “Also, zoning laws are often drawn at the local level so it’s very difficult to change and can’t really change it from a national mandate. The best the federal government could do is provide some incentives to communities to change their zoning laws.”

a lot of this comes down to zoning; changing zoning requirements, increasing the density in some of these areas.

Cristian deRitis

One form of zoning changes is known as inclusionary zoning. “What inclusionary zoning says is that, yes we need development, but the development that happens can’t be at the detriment of the people,” explains Cece Gerlach, Allentown city council member. “What’s happening right now is the development that’s happening down at the waterfront, and downtown is causing the prices in the surrounding neighborhoods to skyrocket.” The money the city has spent on improvements downtown, including a $300 million development by the waterfront, has left a lot of people scrambling for housing.

This development at the waterfront, also known as the Neighborhood Improvement Zone or NIZ, has been criticized by politicians on both sides of the aisle. Says Ramos, “My [concern when the NIZ was first proposed] was that the NIZ’s major players would force out existing homes and businesses… The problem is simple—the proponents of the NIZ tried to make downtown into something that was inaccessible to the large majority of residents. Now, we have to invite local residents to invest in the downtown and make it one that all residents can enjoy.”

“[Inclusionary zoning] just mitigates some of the effects of the gentrification,” Gerlach continues, “it says that for every X number of market rate apartments that developers are building, that a certain percentage of them must be what would be deemed workforce housing. The units must be affordable, must be for working class people, and they must be mixed throughout the development. You can’t have all the working class people on one floor. They must have access to the same amenities and the same quality of life as everyone else.”

Gerlach also explained the kinds of “perks” developers can expect under inclusionary zoning policies. Density restrictions on how tall a developer can build, parking and storage requirements and fees may be partially or fully waived. While these advantages may make constructing new affordable housing more appealing to developers, it isn’t a sure solution in markets that aren’t booming.

“It’s a great solution for places that are building new… you can get economies of scale,” warns Pooley of relying on inclusionary zoning. “But if you don’t have that kind of hot hot market… One of the challenges is that they’ll pass that ordinance and be like ‘Whoo! We have solved the affordable housing crisis!’ You will make 10 families very happy. But you got 30,000 over there who could probably use it.”

Pooley isn’t the only one who is somewhat skeptical about inclusionary zoning. “It sounds nice in theory, and it might work in places where there’s no alternatives,” says Matt Tuerk, Democratic nominee for mayor of Allentown. “But in a place like Allentown, if there’s a requirement that you build 20 percent of your units as affordable, at some additional cost, it’s just as easy to do those projects [somewhere else without the requirement] or just abandon the project and the Lehigh Valley as a whole.”

Ramos is similarly mistrustful of inclusionary zoning, though for different reasons. “Inclusionary zoning is well intentioned but it’s not practical,” says Ramos. “What it will do is give affordable housing to some residents but leave the large majority paying more than they were before. The current housing crisis is caused primarily by government interference in the housing market through gentrification, and more interference is just going to further manipulate the market and drive up rents for the people who can’t get into the subsidized units.”

Though he doesn’t trust inclusionary zoning, Ramos still thinks zoning changes can be a solution. “What we badly need right now are new, affordable apartments. I’m proposing that we re-zone some of our unused industrial space to permit the construction of new, market-rate units. We also need to ensure that government-sponsored development tools like the NIZ aren’t using tax dollars to push out existing residents.”

in a place like Allentown, if there’s a requirement that you build 20 percent of your units as affordable, at some additional cost, it’s just as easy to do those projects [somewhere else without the requirement] or just abandon the project and the Lehigh Valley as a whole.

Matt Tuerk

“People who just lean on zoning as being the solution to everything, it can’t be,” Gerlach acknowledges. “It’s just one tool in the toolbox that when combined with other tools will actually have some type of impact.” Gerlach points out land trusts, nonprofit organizations which own and manage land, and land banks, entities created by the government or a nonprofit group to help manage and sometimes sell delinquent or blighted properties so the lots can be redeveloped for more productive use, like increasing paths to homeownership for low-income families.

As Gerlach pointed out, Allentown is well on its way to developing a land bank, with the first land trust legislation passed this April, aimed at taking delinquent landowners to court and reclaiming the properties, which are then owned by a nonprofit or trust set up by the city. The Allentown Redevelopment Authority may soon be a designated land bank, with funding for property acquisition and rehabilitation mostly acquired through state and federal grants.

Gerlach and Tuerk both also point to the possibility of a points system in order to cut down on bad landlords exploiting subpar properties for extortionate amounts of rent. This proposed system would grade inspections on a scale, perhaps from A to F, and those receiving barely passing or failing grades would receive more frequent inspections. One problem with this system is that Allentown already doesn’t have enough inspectors for the mandated inspections, so increasing frequency for problematic landlords would be difficult.

Tuerk says of the problem, “We’re supposed to inspect our rental units, something like every five years. And I think it’s probably north of eight, and maybe we’re only doing inspections every 10 years. Housing can go south in less than a year.” He also pointed out that with inspections so far apart, landlords have sometimes chosen to pay a fine rather than performing mandated improvements to their properties. Tuerk proposes using the recent $57 million Allentown received from the American Rescue Plan to hire more inspectors and digitize records.

Gerlach also raised the point of an accessible and centralized record of inspections. She pointed out that there is currently no easily searchable record of delinquent landlords for tenants, which leads to households getting stuck in properties that are falling apart with no warning and no easy way out. With a centralized system, tenants have a chance of avoiding getting trapped in leases with predatory slumlords. This would only work if Allentown housing became more available and less competitive, however, because as it stands residents have little choice when it comes to finding affordable units.

DeRitis warns that housing will be locked up for the foreseeable future. “Over the next five to 10 years, you have the millennial population coming of age. The first millennials are in their early 30s now, and that’s right at the prime time for first time homebuyers historically. I believe the age of the first time homebuyer has been around 31 or 32 years. This sizable generation is also the second largest coming of age, entering those prime homebuying or whole household formation years. That’s going to put a lot of demand out there.”

At the same time, their parents, the baby boomers, are not giving up their properties,” continues deRitis. “The dynamics are changing. People want to age in place, hang onto their homes.”

“I don’t see this as a short term issue because of the supply side of the market,” deRitis finishes. “Changing zoning, or even if you have the green light to construct, that’s a multi-year process typically to put up enough homes. This is going to be a problem that’s with us for a while. It is certainly something that everyone needs to be aware of.”

[…] households spending over 70 percent of their income on shelter costs alone.” In Allentown, 54.7 percent of renters pay more than 30 percent of their income towards rent. Meanwhile, rent is expected to […]

[…] Read more from the Muhlenberg Weekly. […]