There is no soft ground around here. At least not since September… early October? It is almost April now. I wish to walk in the grass again (ya know, bare feet, no shoes).

Pennsburg is an interesting place, but not in a particularly fascinating way. Its primarily white (although recently it has become a tad more diverse), working-class population lives in a sort of bubble. The outside world doesn’t really seem to exist. Most people don’t know and don’t really care about much beyond their job and family. Respectable, but also maybe not. Given the current climate.

That being said, you almost can’t blame them. The richest family in town, the Toscos (they own three out of the five pizza places comprising most of the food options, unless you want shitty McDonald’s), seem to only invest in improving their restaurant and buying more real estate. The high school has gotten gradually stricter and seemingly less willing to offer some sort of perspective outside of this five mile stretch. There was a place to make and buy art on Main Street. It’s not there anymore. Next to it is one of the only still-living small businesses, a movie theater we call the Grande. Sometimes the line goes all the way down the block, and other than at Tosco’s or maybe Walmart on a Saturday, I never see so many people in one place. Not here, anyway.

Otherwise, maybe you can go smoke weed in the reservoir (sometimes it smells like crap). There are heroin needles left at the bridge where we sometimes go fishing. We never catch anything, but it’s fine.

Amy Lychock works as a high school art teacher in this small town. Students trust her, they take her class because they like HER (including the “bad kids,” “stoners,” “weirdos”… ya know). She would dress up, she would let you cry in the mini hallway that links her room and the other art studio–a magical place of privacy in a very public school. She would encourage you to make hot chocolate and play music. When you walked through her doors, something felt different than the rest of the building. What is an institution if not a place to become institutionalized?

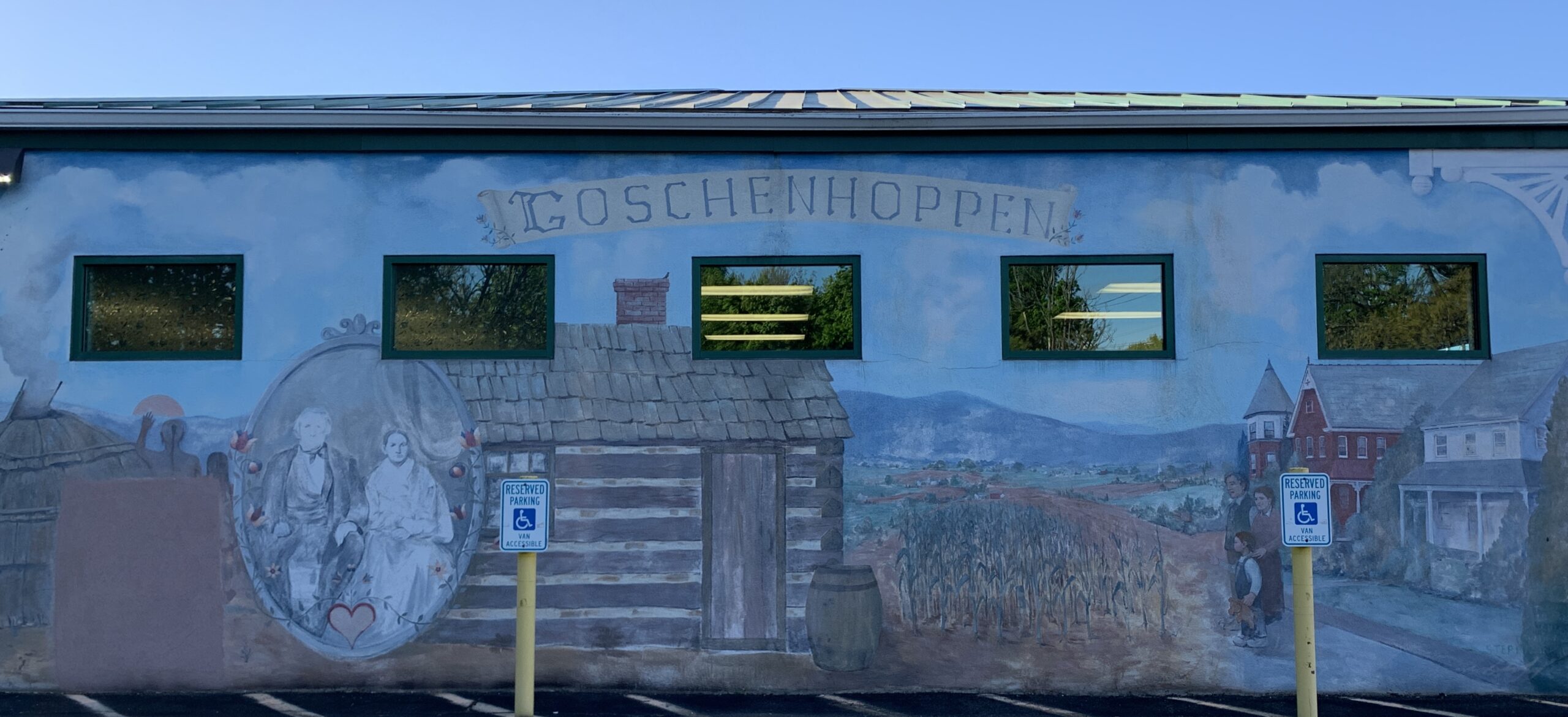

“In like 2005, I worked with a mural artist – we had students working with us too,” explained Lychock about the mural painted on the side of Professional Pharmacy. “It showed the history of that area, so it showed the Lenape, the early [German] settlers and modern times. We did a lot of research on everything, [especially things we may have known less about] like the Native Americans. Everything was meant to be historically accurate.”

As I just listened to her talk about the mural I struggled to really visualize the mural. And I had been stopping at Professional Pharmacy for years. I was a little ashamed. I guess I knew it was there, I just couldn’t picture any details.

For Lychock and her students, this mural wasn’t just a class project. “Doing public art is so much more,” she explained. “Like for me, it’s the connection with the community. And the place it’s gonna be because you have to think, everybody’s gonna see it, the young, the old, they all come here, there was so much discussion.” The goal was to make something that would be meaningful for the people of Pennsburg.

Mural artists (including people like Lychock) want their art to interact with the community.

Frederick Wright Jones, a professor teaching sculpture at Muhlenberg, is one of these people. He is lighthearted, and finds purpose in everything. Both are dedicated to what they do and are unlike anyone else. I am amazed I have been graced to meet them both. Lychock was all love, truth, a real hippie spirit. Jones is all contemplation, expression, a real artist. He talks about public art in a similar sense, its importance, its indefinite definitions, its thoughtfulness, the importance of interaction with it.

Think of social media, but in real life. Some things are memes, and some things you will only see once, some things fade into the background. You’ve fallen from the audience. It can be painted over, or it can sit forever. Public art can become iconic like the LOVE statue, or cut out like Banksy (now it’s ruined, subject to the confines and airs of a museum). It can be the centerpiece like Victor’s Lament at a college campus like Muhlenberg. Or it can be painted over, left to peel away, sedimented. “With public art, what we’re doing is we’re asking to be recognized,” explains Jones. “Making a public art piece is no different than tagging your name somewhere. It’s leaving this artifact, this legacy. It’s something we want to share. We’re in this constant effort to make the world a more beautiful, more livable place and that’s one of those efforts I think.”

The artist sits down and may assess their audience, or their idea, either way they are trying to start a conversation with somebody. Leave a comment but let everyone see it.

This is why it is important that public art continues to change. It brings notice to itself. When something just pops out of nowhere, bold against a dull cityscape, a cafe or bar, you’re bound to look at it.

“Think of the Chinese hand scroll, they are specifically to be looked at or put up for a certain amount of time, no more than a season at most. You notice the fine details of an artwork which just appears or disappears,” explains Lychock. Because its presence in your world is so fleeting, you take the time to examine something that just appears, to interact with it. But art that exists as a permanent fixture in your life is often overlooked, perhaps it requires a change, or perhaps it requires a comment. “You don’t know exactly what the painting that’s been hung up in your house for years looks like,” says Lychock. “It is just there.”

I must have driven up and down Main Street half a dozen times, on separate days, before I finally remembered to stop and really look at the mural. If you’re driving towards the left side of the building, down one of two main roads that make a cross through the town, you can glimpse it for maybe 20 seconds.

I pull into the parking lot and stare at it. It’s really faded.

From a distance, you wouldn’t even know it was documenting anything other than European history. And because of that, it never seemed very interesting. It was something I already knew. “GOSCHENHOPPEN” is sprawled across the top in “We the people of the United States of America” type-font. Under it is a wood cabin, then a field and a London-looking town. To the left of the cabin is a framed couple, the only inclination that there may be any love between them is the delicately drawn heart that sits below them. They are in black and white. All the rest is in color.

To the left of the couple is a large brown square. A singular Native American’s head sticks out from behind it, reaching towards the sun that is going behind the mountains. Their teepee lies beside it, warmed by a fire which lets smoke escape out the top. From the far right, a painted family watches the covering up occur, but they don’t move. Their history will remain.

I think of Dublin, where there are murals everywhere, weaving together different histories. Lebanon, Egypt, and other middle eastern countries, where walls are covered with pictures that show solidarity with its viewers. And I think of Philadelphia, where graffiti means something, and tells stories. Solidarity against corruption. These pieces show history, people’s and place’s essence. A thing just as real as the physical structures these bodies inhabit. It builds community, it brings only good things: increase in jobs, investments, and it’s typically good for the good guy. It is not your big-business industry.

But when I take a closer look at the mural I notice something. That brown square doesn’t belong there. In the last couple of years, someone was offended by the image of the Lenape. Now a corner has been painted over. Once again, history is colonized, west-washed. I’ve often wondered about the decisions which have resulted in this world. There seem to be so many better options. Perhaps we were looking at the wrong art.

So that’s the thing about public art. It can change on a dime, and it comes in infinite forms; standing for a common experience, history, or culture. Sculpture and architecture are often displayed as communal markings, places of habitation, celebrating certain communal ideas and values. Murals appear to be lesser in number, but in recent years, have covered more walls, as grants are given to solo artists, groups of students, and in healthy refutation to graffiti (which perhaps most completely embodies intuitive rebellion, something many artists aspire towards). Most public art initiatives are funded by the government, but since 2001, the number of nonprofit groups supporting public art have skyrocketed. This can create more opportunities for social issues and political statements to be made public. It allows more people to feel heard, outside of the echo chamber that is social media. Something that is both forcefully and gently seen. It is a reflection of the times and the times are a reflection of it.

But what sticks with me the most is a singular sentence from Jones, “Art creates conversation with history.”

Photo by Faith Bugman