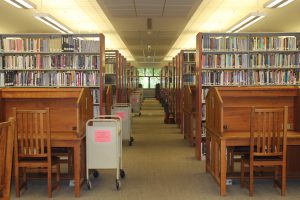

The first thing I notice when I enter Trexler Library, just before finals, is the artificially-hushed atmosphere; it’s quiet, but it isn’t calm, especially now, full of students working and studying, the only sound the urgent chattering of fingers on keys. On A-level, where talking is tolerated, there are small groups scattered throughout the tables; one cluster of sweatshirt-clad students is having an animated discussion; quietly, but with an occasional, stifled shriek of laughter. One floor down reveals the loners, the intensely focused, and here there are actually a few students hiding in the stacks. However, none of them appear to be reading anything from the shelves; one girl is sitting on the floor with her laptop and papers spread around her. She is simply taking comfort in the presence of the stacks around her; presumably, for her and many others, it’s an environment conducive to focus. I’m not brave enough to take on C-level, that silent dungeon — it’s too quiet, it’s suffocating.

In some places Trexler Library smells like old paper on even older shelves; in others like fresh ink, carpet glue, plastic chairs. Some parts of it are classic; in places high-ceilinged, built out of dark, glossy wood with a parquet floor. Some parts are modern and ergonomic. Are these structural components – the chairs, the tables, the space- what makes the library? Would it be a library no longer, if the building were used solely for collaboration space, the collections digitized? What would Muhlenberg be without any books?

Ideas of what makes a library are rapidly changing as the needs of their patrons change. Libraries are more than warehouses full of paper, they have always been collaborative, communicative spaces. “Different disciplines rely on information use and knowledge production in different ways,” says library director Tina Hertel, “The arts and the humanities rely more on print and books, while the sciences may rely more on journal articles, which can be easily accessed via digital formats.” Because of this range of needs for a range of formats, students and faculty at many larger universities across the United States and the world are pushing for major changes to their school libraries: more study spaces, more technology, more Silicon Valley-style nap pods and cozy nooks with bean-bag chairs, where headphones are required and coffee is encouraged. To make literal space for these changes, they are also pushing for fewer books. The operative word here is fewer.

Schools have many reasons for the drastic change: making room for collaboration spaces at UC Berkeley and UCLA, desperately needed classrooms and study spaces at UC Santa Cruz, the increasing financial strain (one 2009 study cited in the Chicago Tribune estimates a cost of $4 per book to keep it on the shelf for a year), and the weeding of books that are rarely, if ever, read, which depleted Indiana University of Pennsylvania’s library by approximately 170,000 volumes. For perspective, that’s more than half of Muhlenberg’s collection – and the school received some backlash from its faculty who wished to save the volumes. But as one student at IUP said to the Chicago Tribune, “If nobody’s reading them, what’s the point of having them?” Many students are appreciative of the increasing workspace and its amenities. At Berkeley, the Moffitt Library was removed in its entirety to make room for student spaces; this may seem drastic, but it’s all about perspective: the Moffitt Library was not UC Berkeley’s main library – it was a special collection and depleted a mere 130,000 volumes of Berkeley’s total 12.4 million print volumes. It was hardly a dent, and as a spokesman for UC Santa Cruz said, after the school purged 80,000 volumes which made up the Science and Engineering Library, “nothing has left the scholarly record.”

Large research universities not only have access to nearly everything in their collections online, they also feel pressure to upgrade that a small liberal arts school like Muhlenberg may not. The question is, are these spaces still libraries? Perhaps it depends on our perceptions of tradition, of scholarliness, and of finding that perfect book that completes some puzzle that keeps us clinging to the dusty spines; people who love to read and love libraries know that feeling of falling into a new book and devouring it, like a kind of euphoria, and there is a deep emotional connection to paper books themselves. That connection, however, does not negate the need for a new kind of library; it has to adapt to available technologies, there is need for high-tech collaborative workspace accessible to students at any time. As for the buildings themselves, communities still need that physical space, a safe space, one that is just for focus and learning – the stacks can be digitized, that environment and atmosphere cannot. That said, studies such as this one from the Pew Research Center show that print books are still in fashion.

Trexler Library recently conducted a survey asking whether people preferred to work from print or digital editions. The responses varied based on the purpose or reason for using a particular resource. For shorter readings, such as news, reference/fact-finding, or journal articles, many respondents prefer online (almost 75 percent); for longer reads such as entire books or materials for leisure reading, more than 75 percent prefer print over online access. Even for those shorter reads, between 13 percent (reference/fact-finding) and 18 percent (journal articles) prefer print over online.

“Do libraries still need books?” says Tina Hertel, “Absolutely. While more is certainly available digitally, not everything is available digitally. Overall, preference is still for print material.”

Hertel adds that circulation numbers here have remained fairly consistent during her time here. Students account for the most checkouts, though faculty understandably account for more checkouts per person. It’s a difficult statistic to exact, however; many of the library’s materials are used within its walls, known as a “soft checkout” because the book is never officially lent. This speaks to the library’s varied resources; it is a place to read and write and think, not just a book-storage. “Libraries have long been associated as being keepers of the books, but that is the immediate image that comes to mind, just as we have preconceived notions of what a hospital is or a grocery store is,” says Hertel. “The library has long been more than a storehouse for books. Libraries are about information, and it just so happens that for a very long period of time much of that information was held in books.” She elaborates on the many forms knowledge takes in today’s academic world, and at our own school: audio, video, images, scores, music, art, and more. “What [going] digital really helps with is access. We can access so much more information…and often even when people access it digitally, they will print it out to best interact and engage with that information,” Hertel says.

“I think we are aware that there is a trend in libraries for more collaboration spaces,” says Trexler Library’s Special Collections and Archives librarian, Susan Falciani Maldonado, “I think that there is the possibility [here] of a slight reduction – we are always weeding – but I do not believe that the collections are going to be reduced significantly. We are constantly assessing these spaces and trying to be responsive to the campus community while still maintaining the intellectual heart [of the library]; for librarians, as guides and curators of information, finding it and making value judgements about it, and teaching students how to be smart consumers, is something we have evolved with and we will continue to do so…It is a community that adapts well to change and is happy to be to the navigator through information,” Falciani Maldonado provides a perspective that pinpoints the middle ground that Muhlenberg occupies between the need to make space for new things and the significance of our collection. At UT-Austin, the community demanded a 3-D printing lab; Muhlenberg just doesn’t need those kinds of resources. “While our library budget is higher for online resources, such as online journals, ebooks, streaming content, databases, etc. than for print and physical resources,” emphasizes Hertel, “that is because the library is more than books. The library is about access–universal and equitable access.”

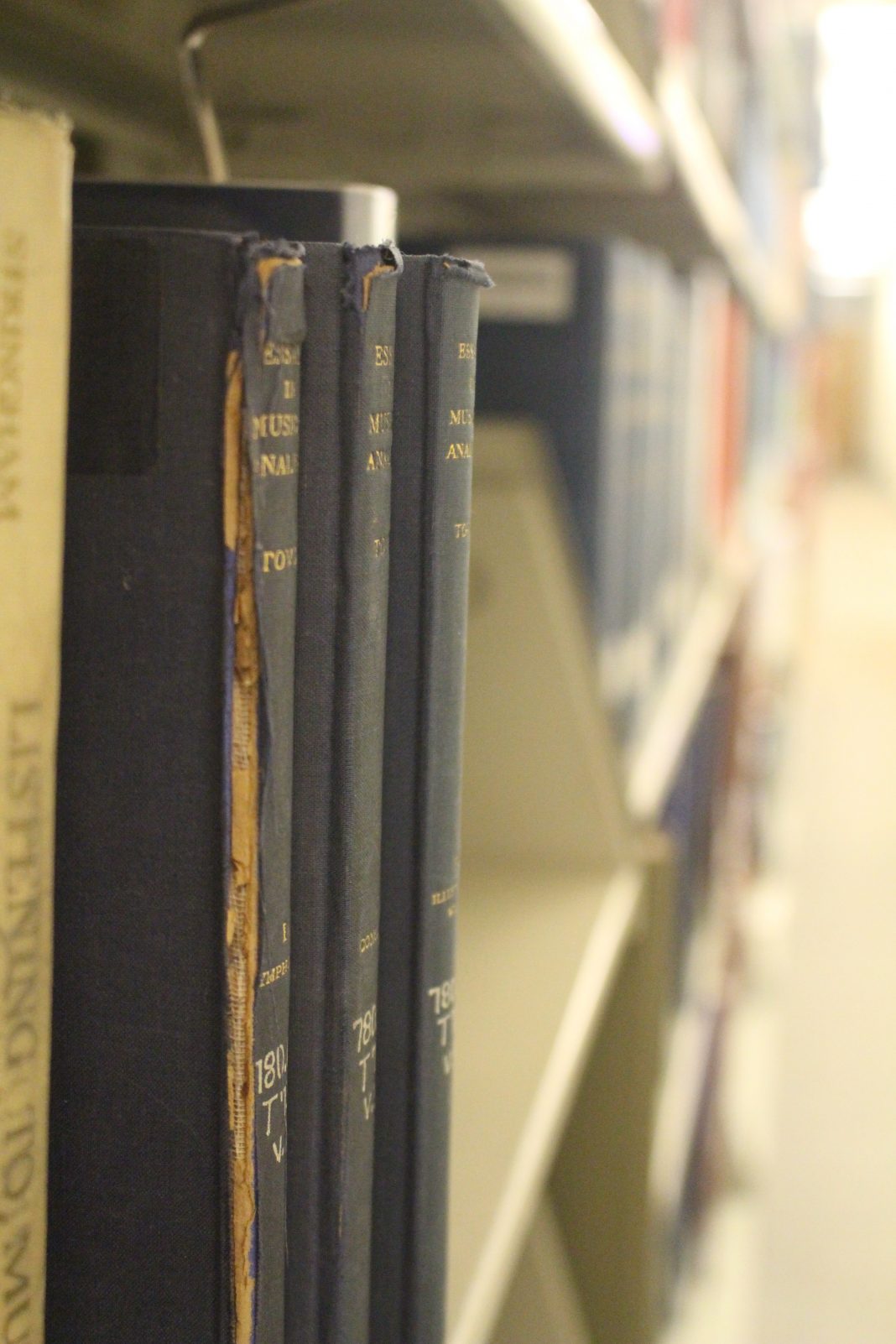

Digitization can only go so far, however. Print media still dominates at Muhlenberg: Trexler library boasts 310,000 print volumes and 29,000 print- and e-journals. Digital versions of print books, though useful, can also never replace the feeling of leafing through a book, the same book that another student held a hundred years ago. Muhlenberg’s library houses an impressive, awe-inspiring rare books collection that is impressively underappreciated by the student body. If you descend the narrow staircase in Trexler Library’s Muhlenberg Room, you’ll find yourself surrounded by glass cases displaying Reformation-era Lutheran texts, including one signed by Martin Luther himself. This is the Rare Books exhibit room, a small, peaceful corner of B-level, where, one morning, I found a lone student deep in work on her laptop. She was using the otherwise empty display room as a study space, and clearly had little interest in the cases of books or the interview I conducted there. To either side of the room there are discreet doors, windowless and locked and oozing potential. These rooms contain the majority of the collection, of which the displays are only a small part. If you are lucky enough to gain access to this vault of collected knowledge, the lighting softens; the air is cool and dry, and carries that sweet, musty smell of ink on old paper, leather bindings covered in gold paint; you can almost hear the ghosts of everyone through whose hands these books have passed. I gingerly turned the pages of first-edition Hemingways, I slid my fingers over an embossed copy of Pride and Prejudice, and it felt like a privilege I hadn’t earned. Huge, ancient bibles are stacked sideways there, wider than floorboards. Falciani Maldonado tells me about three volumes of incunabula, books published within the first 50 years of the invention of the Gutenberg printing press.

“We have books here from 1485, and that is pretty cool,” she says. “I wish I could spend all my time with the rare books collection…If I could clone myself…I know there are more connections to be made. Being in a position where the light bulb can go off for students, touching history, and thinking about it and writing about it and doing projects around it, is the best thing my gifts could ever be used for.” She is getting to the heart of what makes a library: a place, built from collaboration, that can teach and inspire. “We are about innovation,” adds Hertel. “We are about cultivating curiosity. And more importantly, libraries are about the people — the librarians who teach the critical skills necessary to navigate an ever-evolving information landscape, the staff who provide a variety of library services, the faculty who expand the course content with a strong library collection, the students who are developing as lifelong learners, the researchers who love the primary materials, the bookworms who read voraciously, the actors who practice their lines, the musicians who study the scores of masters before them, the citizens who read the newspapers, the people studying their genealogy, the unemployed rewriting their resume, and the list goes on and on…”

Keeping this sanctity in mind, I went back to the library, to do some work (on my laptop) and browse the stacks. I sat once more on A-level, blending into the crowd of students, absorbing their restless energy. Low rumblings from each group penetrated my headphones; the strips of fluorescent light pressed hard against my eyeballs. I found myself distracted, reading the Greek letters carved into the table like ancient runes. I thought about how many students have been in this exact chair, probably equally overstimulated. I got up for a walk around the stacks, hoping to stir some blood back into my brain. Titles jumped out at me from their shelves: 500 Years of Printing, impossibly slim; Mystery, Magic, and Medicine, re-bound in a plain black jacket; Russian Decorative Folk Art, a huge hardcover volume. Finally, a fraying grass-green book caught my eye, its spine embellished with golden holly leaves and vines. The title: The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne. I plucked it from the shelf, curious. It’s a 1906 first edition, an anthology of letters exchanged between an amateur naturalist in the parish of Selborne and his friend in London, detailing, mainly, the mysterious activities of the migratory birds of England. I love the way the book smells, antique and sweet like soil. I like the way some words have extra vowels, as if their writer dipped his pen into the early modern English of the century before, drawing on tradition and cementing a certain flair. The book was too charming to place it back on its shelf, so I carried it with me back up the stairs. I wondered when the book was last borrowed; I found myself wishing we still used the ink-stamp method, the lending card in the back of the book is blank, the digital record of its use not immediately available. I wonder if it’s ever been checked out by a student, and I know now what I have to do; not for myself, or for Trexler Library, but for this book itself. For all the forgotten books.